Paloma Proudfoot, Anna Perach, and Marc Camille Chaimowicz works blur the boundaries between art and craft, public and private, body and object, inviting us into spaces where personal histories and collective memory entwine.

Material Worlds: Contemporary Artists and Textiles is a free group exhibition featuring radical and exciting contemporary artists using textiles to explore ideas of the body, identity, gender, race, heritage, myth and folklore. The potential of textiles as an art form has been pushed to extraordinary limits creating works that are theatrical, bold, unsettling and humorous.

Anna Perach

Anna Perach is a Ukrainian-born artist, who is now based in London. She received a distinction in MFA in Fine Art from Goldsmiths, London, in 2020. Her short career has already seen remarkable success, with solo exhibitions at Gasworks, London (2024); Ada Gallery, Rome (2023); and Herzliya Museum of Contemporary Art, Israel (2021.) She is also highly accoladed, having won the Hopper Prize (2023) and The Ingram Prize (2021.)

Anna Perach’s favoured medium is tufting, a technique traditionally used in the fabrication of carpets. With its long-established connection to domesticity and ‘femininity,’ Perach confronts patriarchal expectations by incorporating subversive and shocking subjects. Instead of the delicate, soft, beautiful pieces we have come to expect, we are met with beastly, shocking or sensual sculptures. These unexpected elements often examine how women’s bodies and behaviour have been historically inhibited; whether with corsets, beauty standards, or even subversive women being labelled as witches and brutally punished. Venus, the work featured in the Material World’s exhibition, criticises eighteenth-century wax sculptures known as ‘anatomical Venuses.’ These hyperreal sculptures of women were intended to aid medical education as they allowed for the exploration of female anatomy. However, these beautiful, naked models became the focus of eroticisation and desire, perverting their intention and highlighting the predation and vulnerability present in the medical field.

Her pieces are therefore acts of transgression and resistance. Indeed, Perach’s sculptures recall the fantastical pagan “wild men” costumes worn at traditional festivals in mountainous regions of Europe. Yet these colourful creations are undeniably wild women—nonconforming and rebellious. In Eastern Europe and the former USSR territories, textile art enjoyed less governmental censorial scrutiny, giving women power to weave and sew small acts of rebellion. Perach has therefore continued on this impressive insurgent legacy.

Gender, however, is not her sole focus; she also aims to examine senses of self. Her sculptures can also be worn by performers, transforming not only the piece but equally the model. The carpet becomes another layer of skin, suppressing the identity of the person, yet in this anonymity, it allows fragments of the self to emerge in exciting and unexpected ways. It becomes slightly uncanny; the idea of selfhood is stretched to increasingly broader boundaries. She particularly engages with the dynamic between personal and cultural myths; ‘specifically l’m interested in how our private narratives are deeply rooted in ancient folklore and storytelling.’

Material Worlds features two of Anna Perach’s pieces: Venus (2023) and Glove (2023.) Her works, as mentioned, are not only life-size sculptures, but can be worn as costumes. Yet Venus, when not used in this performative way, becomes a hollow, sagging sculpture that is eerie and disturbing. Life-like, but devoid of life. There is a profound sense of gore and unease, as colours contrast with red, sore nipples, a clown-like face with exaggerated lips and a gaping tear revealing organs. A panel on her abdomen unzips to reveal silk, glass kidneys and a curled glass foetus all nestled into leather viscera. Perach here incorporates different materials, using beads, artificial silk, cast and blown glass and selvedge leather, which contrasts these delicate, precise interior organs with the highly tactile feminine body. Hung on the wall beside her is a blood-red gauntlet, ready to be plunged into this exposed interior. The piece allows for a strong sense of voyeurism as we spy on the naked Venus and become complicit in the patriarchy.

Paloma Proudfoot

Proudfoot received a BA in Sculpture from the Edinburgh College of Art and an MFA from the Royal College of Art, London. She has gone on to have solo exhibitions at the Soy Capitan Gallery, Berlin, Germany (2023); Soy Capitan Gallery, Turin, Italy (2023); and group exhibitions at the Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art, London, UK (2023); ‘In Watte und Nadeln—Konturen von Trauer (Contours of Grief),’ Galerie im Koernerpark, Berlin (2023); Soy Capitan Gallery, Art Duesseldorf, Germany (2023.)

Throughout her career, Proudfoot has combined sculpture with textiles, performance, and text, navigating a space where materiality meets metaphor. In recent years, her practice has seen a notable shift, particularly in her use of ceramics. Rather than treating ceramic as a traditionally three-dimensional medium, she manipulates it into sheet-like forms that resemble cut patterns from garment-making. Employing techniques akin to flat pattern-cutting, she creates delicate templates from which she casts these pseudo-fabric ceramic pieces. By incorporating additional materials, such as metal, ribbons, scrunchies, and other fabric elements, she builds layered, hybrid works that mimic textiles while subverting expectations of ceramic’s hardness and fragility.

Central to Proudfoot’s work is the relationship between the body and garments: how textiles can function as both protective layers and intimate signifiers. Her exploration of this relationship reveals themes of vulnerability, transformation, shame, care, and resilience. She often uses fragmented forms and figurative tableaux to suggest the emotional weight carried by the human body, both as a physical site and as a narrative vessel. Her recent works, such as Skin Poem (II) and A Casting From Life, foreground a sense of collective compassion, with figures depicted in states of kinship and gentle communion. These moments of touch and connection speak to the artist’s ongoing interest in the power dynamics between bodies and how tenderness can be a radical, reconstructive force.

Her work also draws from a deep engagement with the histories of gender, medicine, and display. Proudfoot frequently interrogates the way women’s bodies have been demonised, fetishized, and controlled; particularly in medical and cultural institutions. This research has led her to study the 19th-century theories of neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot, whose work at the Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris involved controversial clinical performances of women diagnosed with ‘hysteria.’ Proudfoot reinterprets such histories through her materials, echoing the objectification of the female body in mannequins, anatomical models, and tailoring patterns; yet imbuing her sculptures with emotional nuance and empathetic intent.

A recent example of this approach is her 2023 piece Laced, currently exhibited at Lakeside Arts. The work is emblematic of her continued exploration into the intersections of textiles, ceramics, and bodily experience. Laced presents a ceramic form shaped and styled to echo the construction of a corset or undergarment; intimate clothing that traditionally constrains and shapes the body. Here, the piece becomes a metaphor for the push and pull between containment and vulnerability, its rigid ceramic surface belying the softness of what it represents. Ribbons, ties, and apertures imply both functionality and fragility, suggesting that identity itself is something stitched together from tension, memory, and gesture.

Through Laced and her wider body of work, Proudfoot demonstrates that sculpture is not just a form to behold, but a language; one that can speak to histories of care, control, and connection. Her practice challenges the viewer to reconsider the emotional resonance of everyday materials and the stories our bodies, clothes, and objects continue to carry.

Marc Camille Chaimowicz

Born in postwar Paris to a Polish-Jewish father and French-Catholic mother, Chaimowicz moved to London at the age of eight, a bi-cultural upbringing that would later deeply inform his work. He studied at Ealing School of Art and the Slade School of Fine Art, where his political and aesthetic convictions took shape amid the post-1968 cultural climate. Refusing the macho austerity that defined much of conceptual and leftist art at the time, he turned instead to colour, softness, and domesticity as radical artistic strategies. Over his career, Chaimowicz held solo exhibitions at institutions such as the Serpentine Galleries (London), WIELS (Brussels), Kunsthalle Bern, and the Jewish Museum (New York). His work is held in major collections including Tate Modern, MoMA, and the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Chaimowicz’s practice was resolutely multidisciplinary, encompassing painting, sculpture, furniture, ceramics, wallpaper, textiles, writing, photography, performance, and installation. He challenged the hierarchy between the applied and fine arts by celebrating decor and design as vehicles for emotional and political expression. Pastel tones, delicate patterns, floral motifs, and luxurious textures recur throughout his work, as do intimate, crafted objects, coat hooks, chaise lounges, screens, that blur the boundary between artwork and domestic artifact. By staging his works in carefully composed interiors, he invited viewers to inhabit a world where softness, beauty, and ambiguity could assert artistic and political significance.

Thematically, Chaimowicz’s work is deeply engaged with identity, memory, intimacy, and transformation. His installations evoke private spaces imbued with associative meaning: a boudoir, a sitting room, or a salon filled with traces of past inhabitants. His use of femininity, through colour, texture, and gesture, was both reverent and subversive, challenging prescriptive norms of gender and taste. He often explored the fluidity of self: the overlap between public and private, masculine and feminine, cerebral and sensual. A passionate reader of Jean Cocteau, Jean Genet, and Roland Barthes, Chaimowicz infused his work with literary and autobiographical allusions, weaving together personal narrative with broader cultural histories. As critic Tom Holert noted, his work questioned “the role of the artist, who in this defining work simultaneously becomes art director, choreographer and participant.”

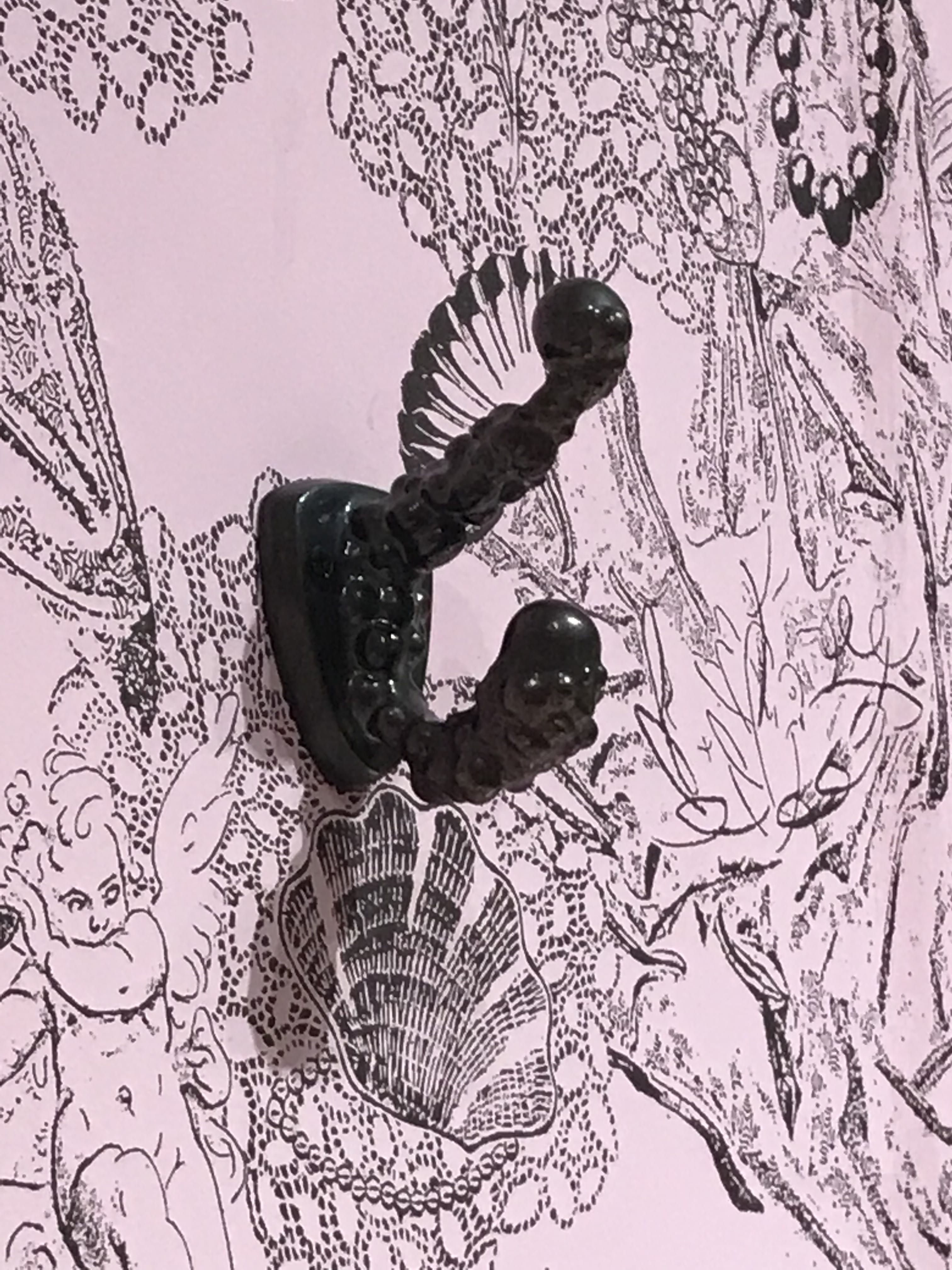

This multifaceted approach is evident in three works on display: Dual (2006–07), Malevolent Coat Hook (2005), and Cluny (2006).

Malevolent Coat Hook (2005) is deceptively simple: a domestic object that hints at psychological tension. The word “malevolent” clashes with its practical form, suggesting how objects in our homes can carry emotional charge or latent threat. Like much of Chaimowicz’s work, it challenges viewers to see the everyday as poetic, or quietly unsettling.

Dual is a modular seating arrangement that shifts between two chaise lounges and a pair of armchairs. Set against custom-designed wallpaper, the piece functions not only as furniture but as a performance of transformation, an homage to Jean Cocteau and a meditation on the fluid nature of identity. Its reversible, morphing design reflects Chaimowicz’s long-standing interest in ambiguity and duality, evoking his own position between cultures, languages, and genders.

Cluny (2006), named after the medieval Musée de Cluny in Paris, draws from historical and art-historical references, reinterpreting motifs of European decorative arts through a modern, queer sensibility. Both reverent and playful, the piece invites reflection on how history, design, and identity are layered into our spaces and selves.

Together, these works exemplify Marc Camille Chaimowicz’s singular vision, one that celebrated beauty, softness, ambiguity, and interiority as sites of resistance and revelation. In transforming the personal into the political, and the decorative into the critical, Chaimowicz expanded the possibilities of contemporary art and left behind a legacy that continues to inspire.

The Material Worlds exhibition is open to visit until 31st August 2025 at the Djanogly Gallery, Lakeside Arts. Find more details here.